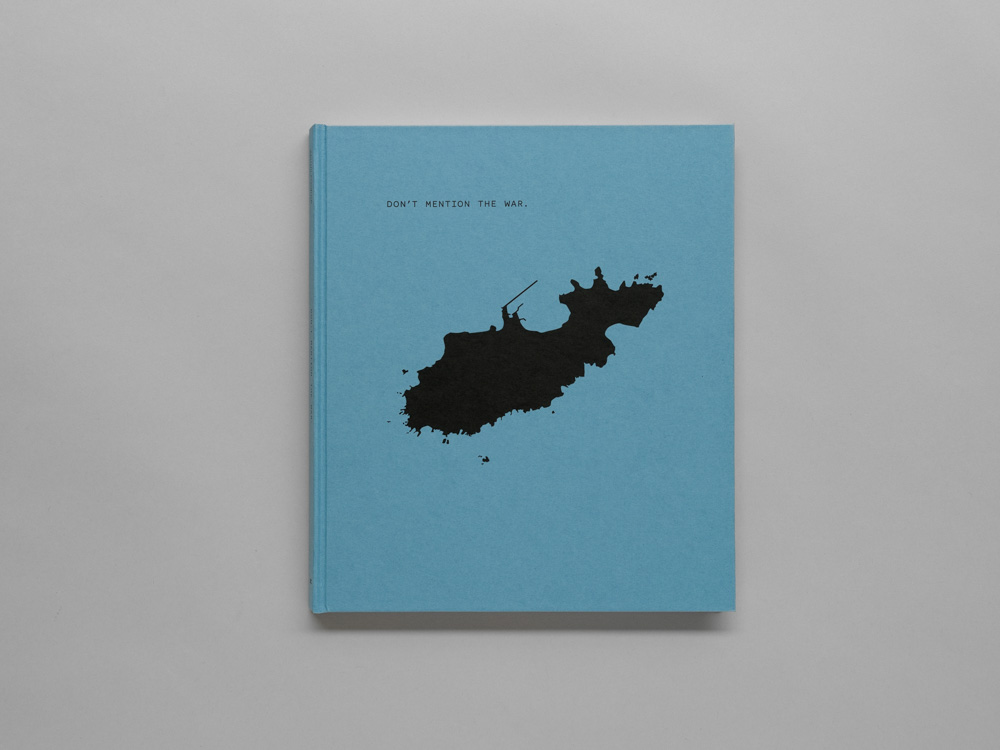

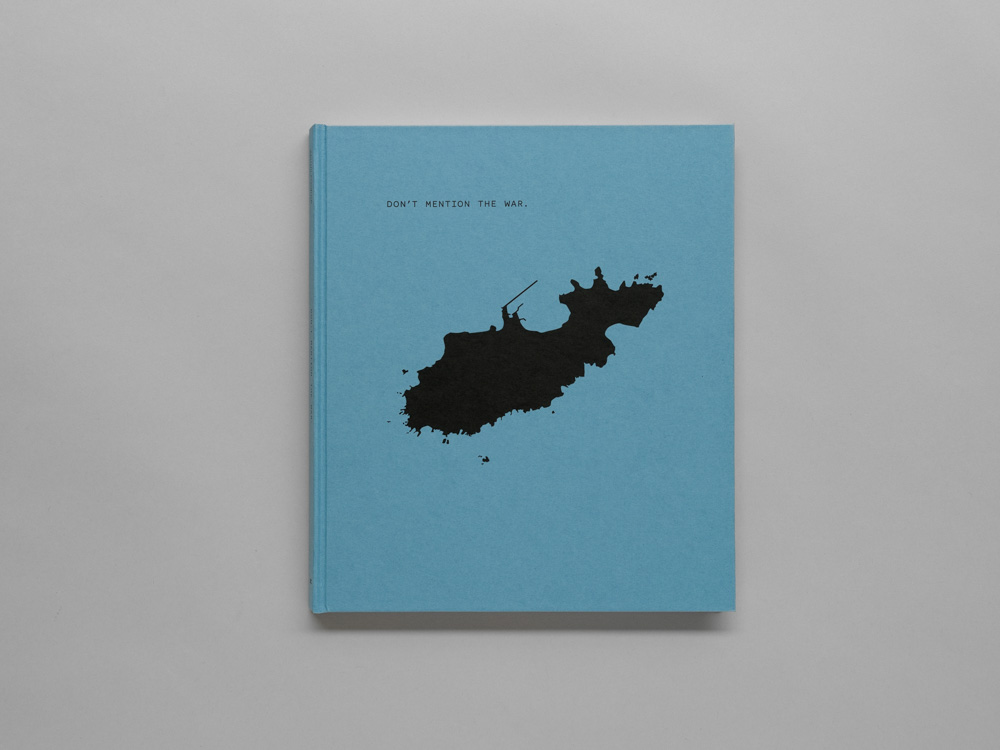

Don't mention the war.

(2015–2018)

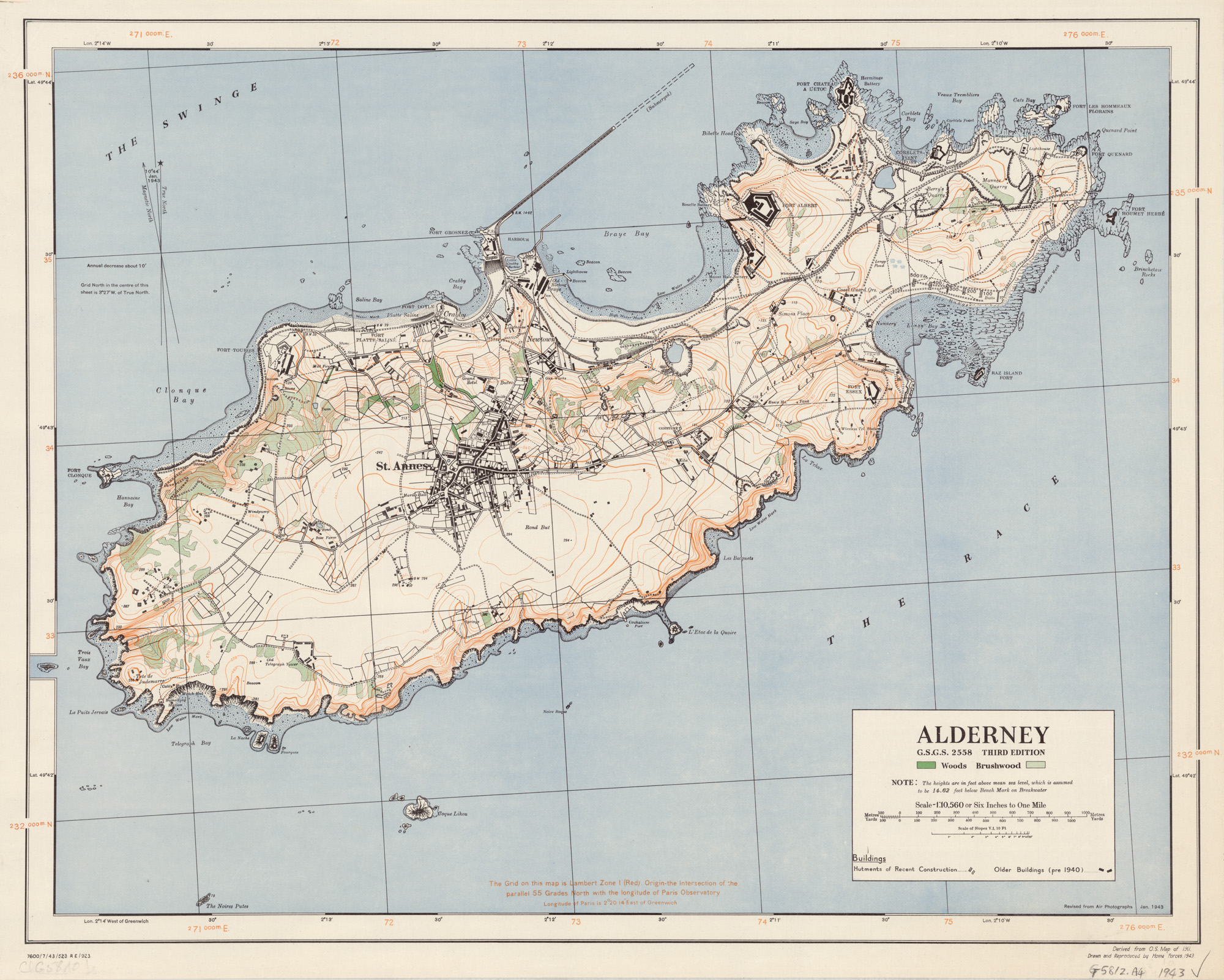

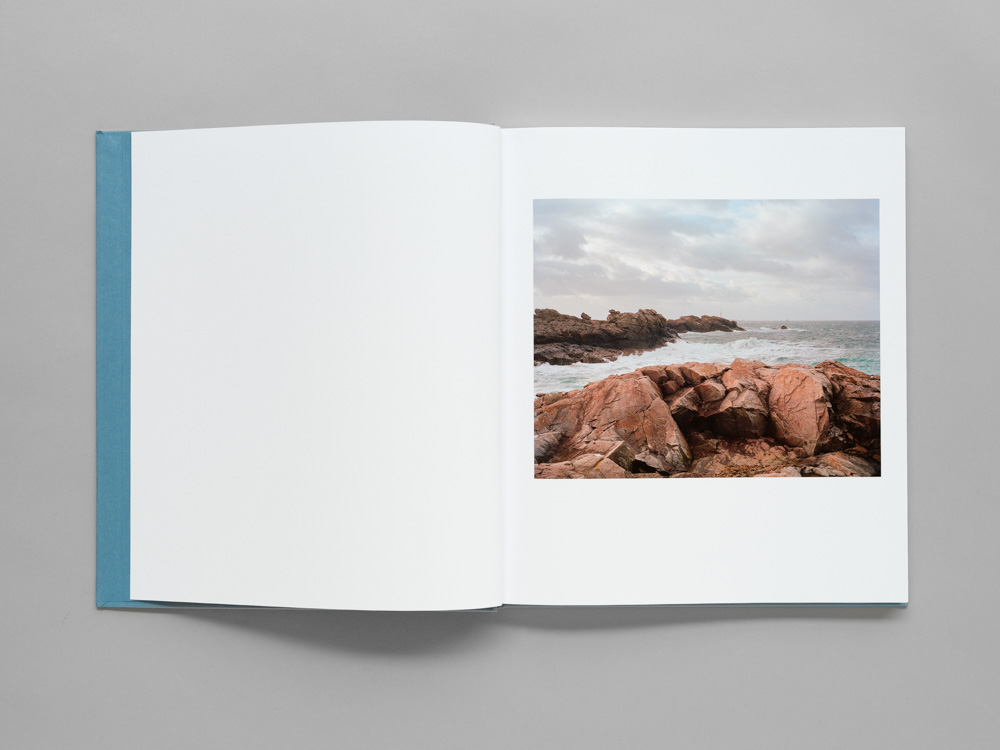

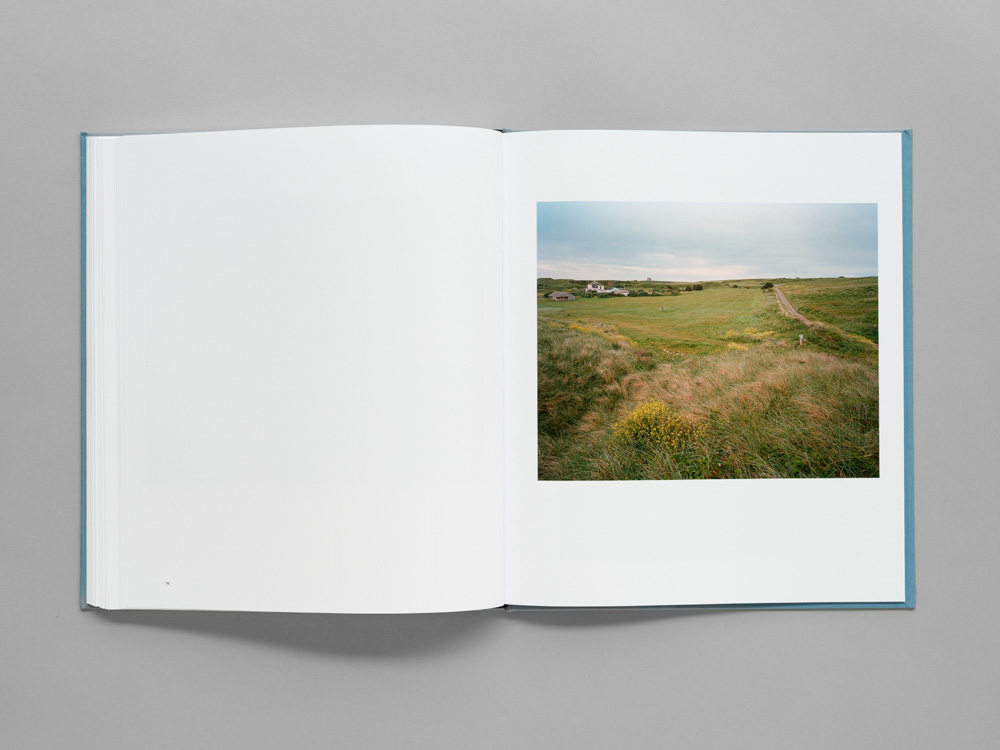

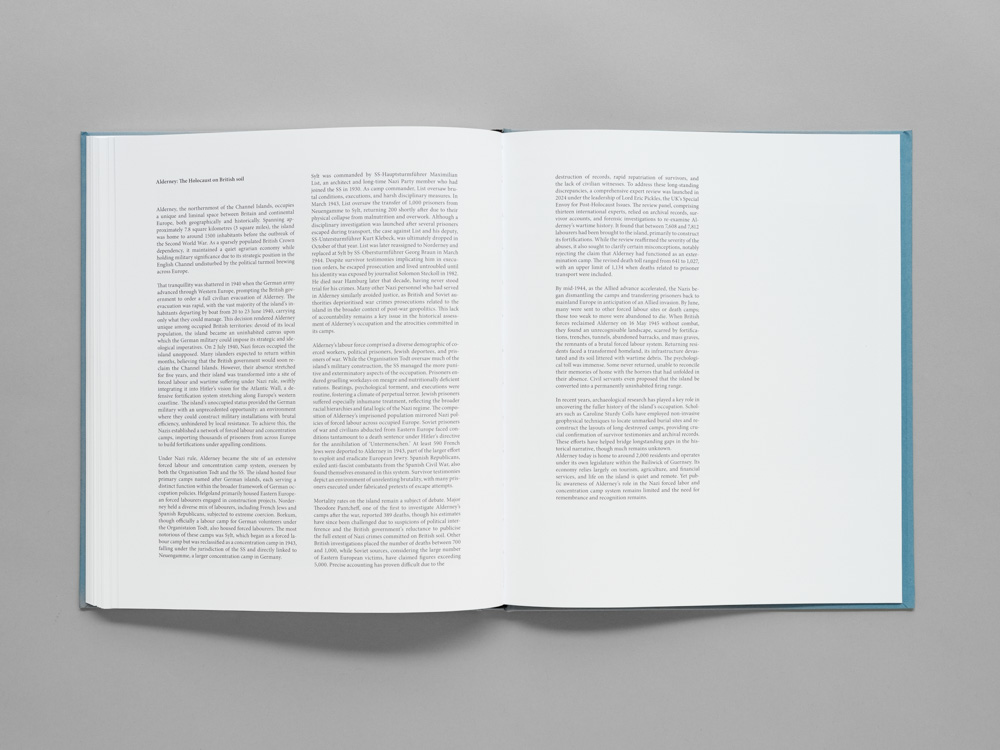

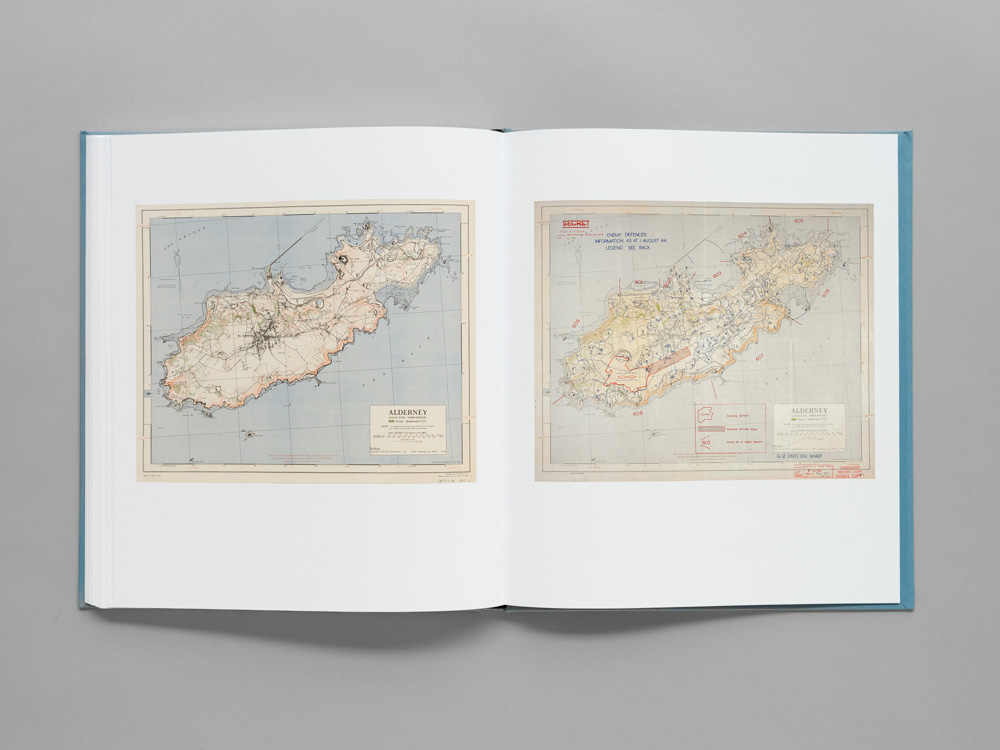

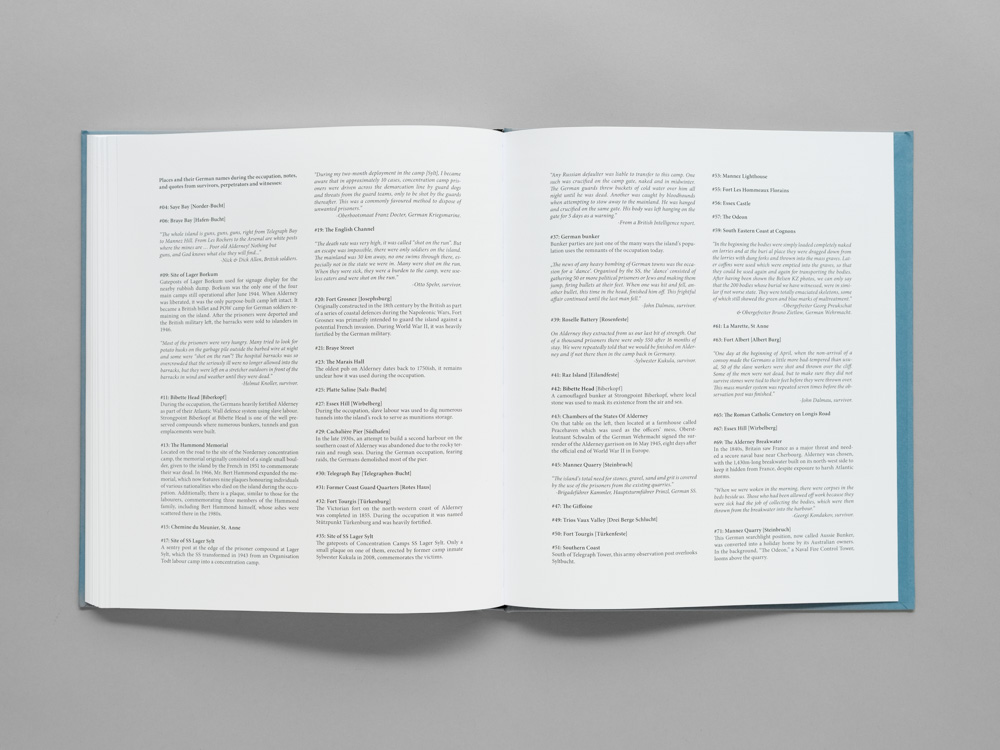

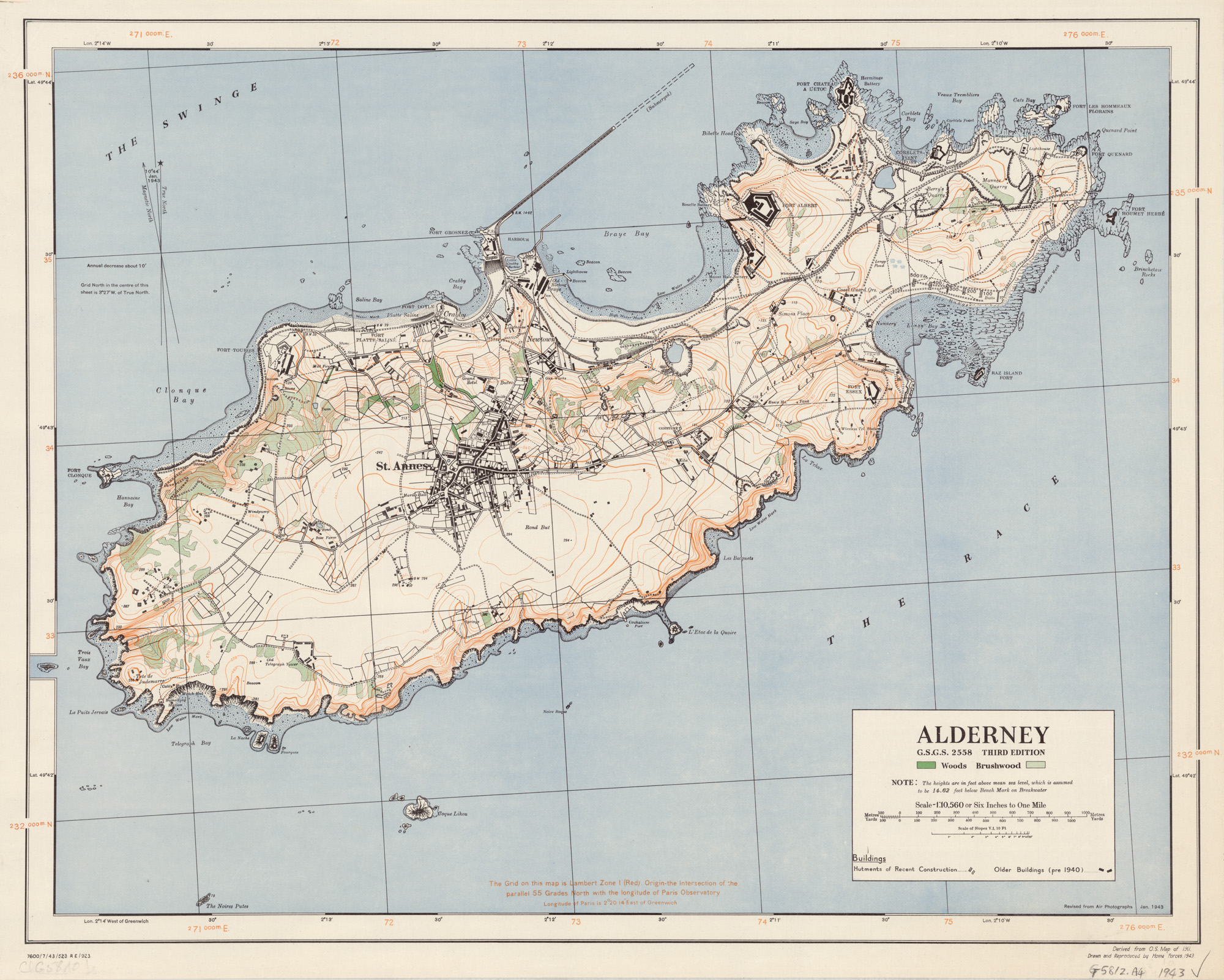

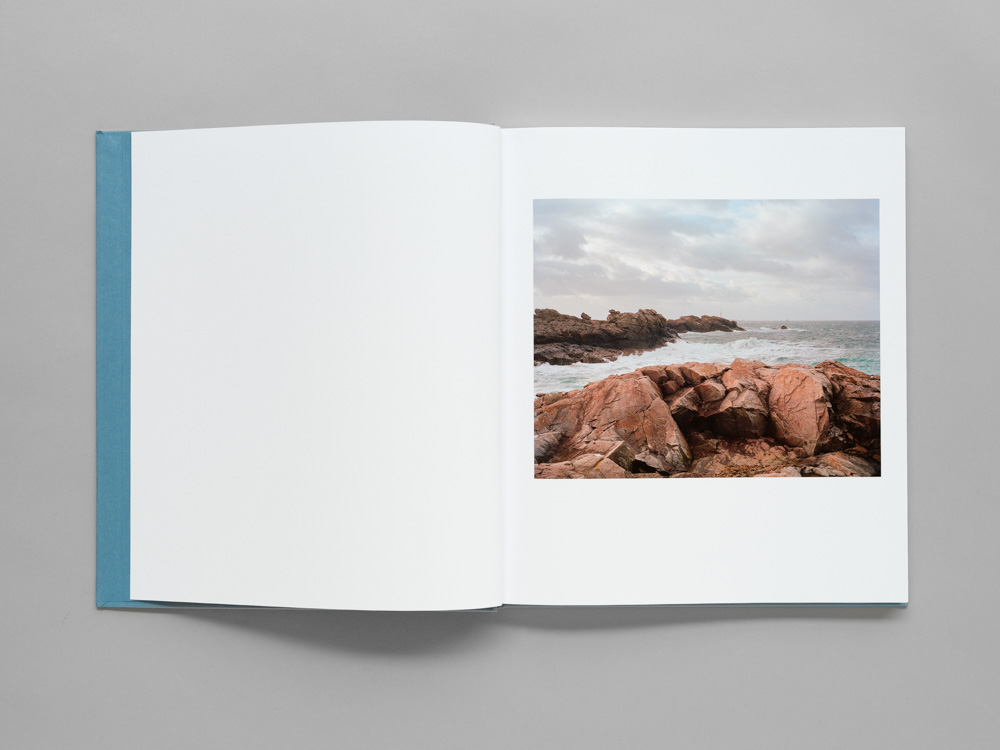

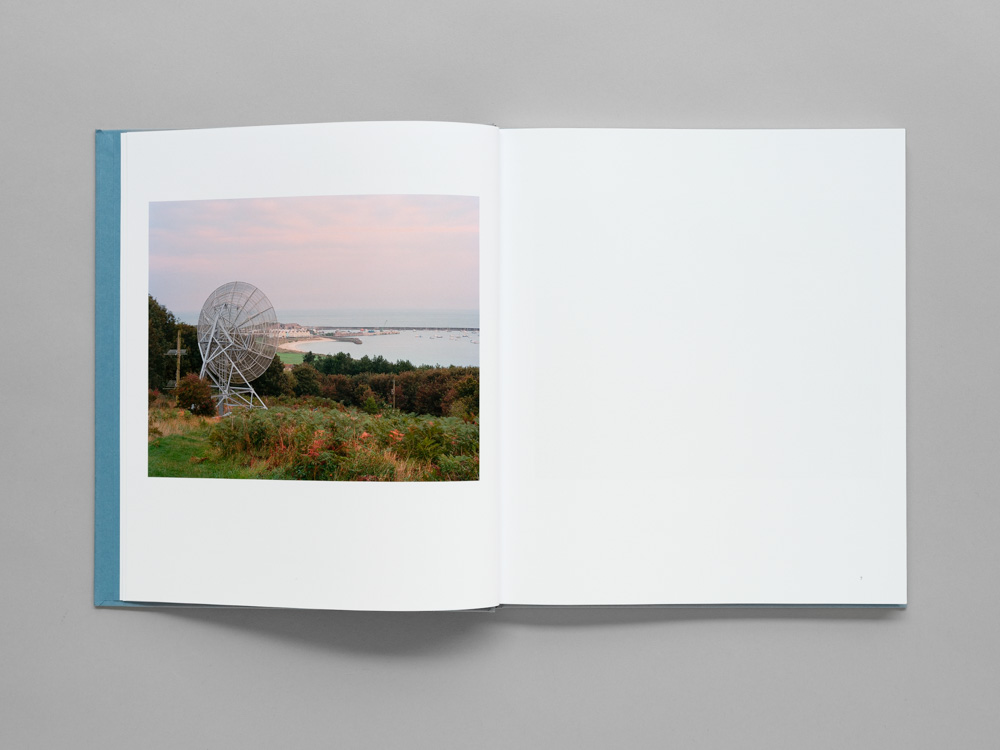

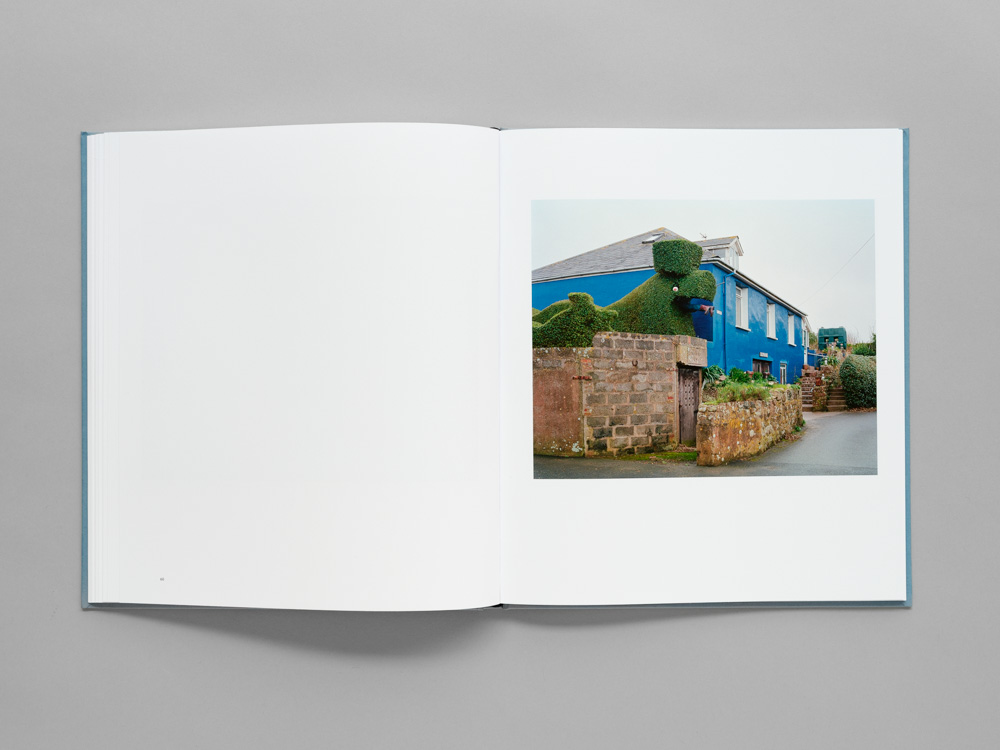

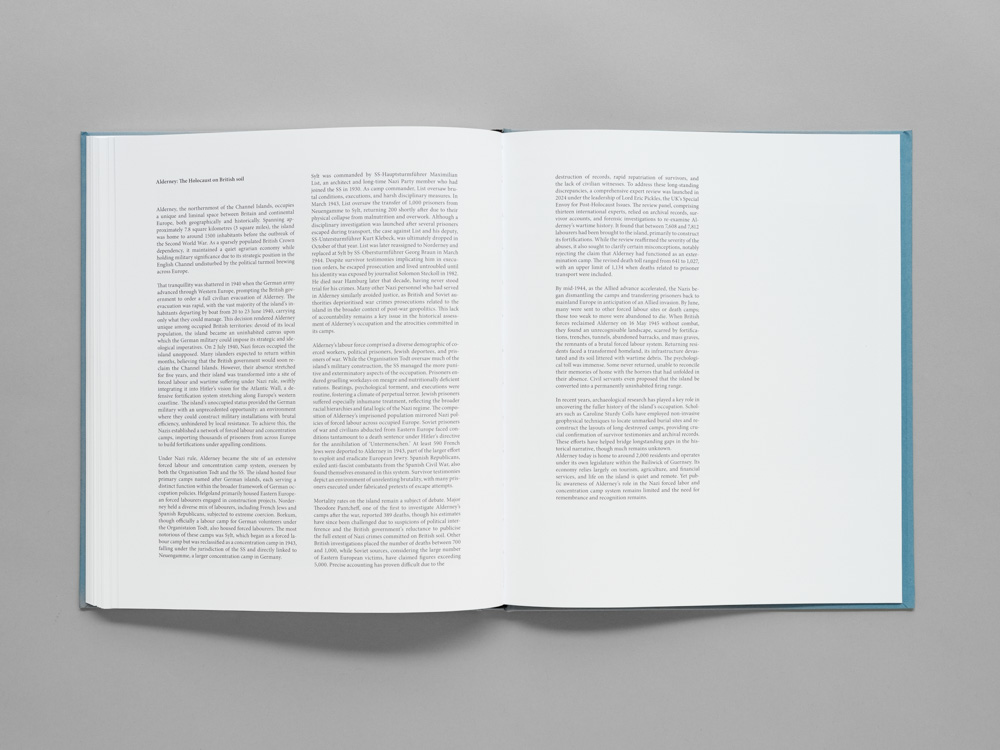

Alderney, the northernmost of the Channel Islands, occupies a unique and liminal space between Britain and continental Europe, both geographically and historically. Spanning approximately 7.8 square kilometres (3 square miles), the island was home to around 1500 inhabitants before the outbreak of the Second World War. As a sparsely populated British Crown dependency, it maintained a quiet agrarian economy while holding military significance due to its strategic position in the English Channel undisturbed by the political turmoil brewing across Europe.

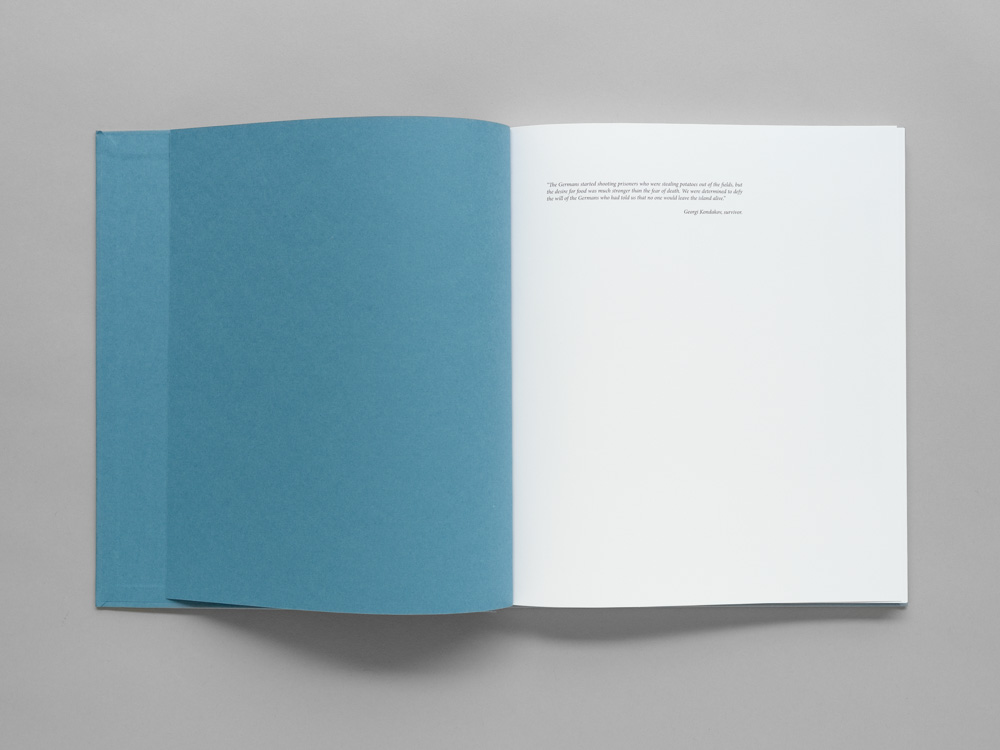

“The Germans started shooting prisoners who were stealing potatoes out of the fields, but the desire for food was much stronger than the fear of death. We were determined to defy the will of the Germans who had told us that no one would leave the island alive.”

Georgi Kondakov, survivor.

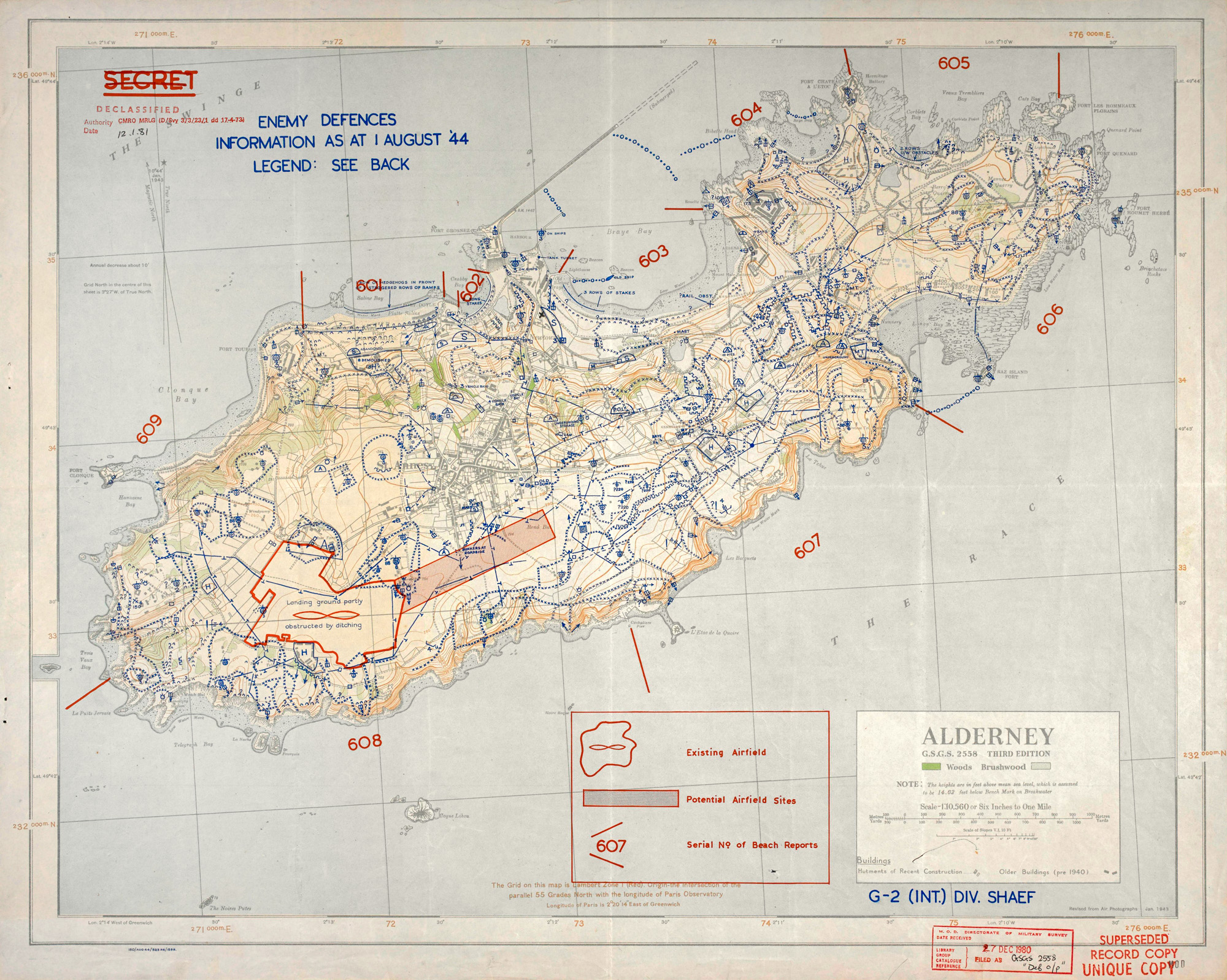

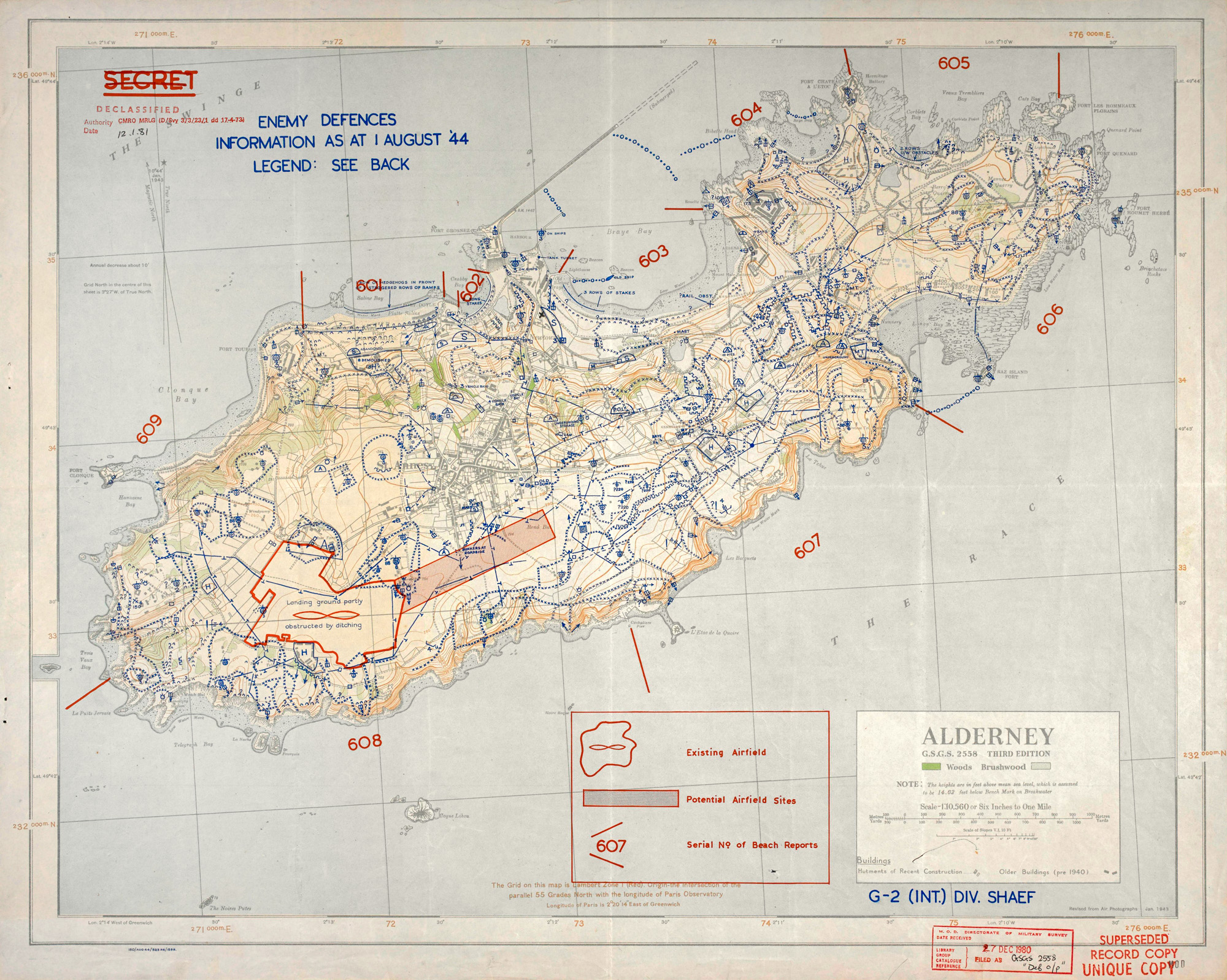

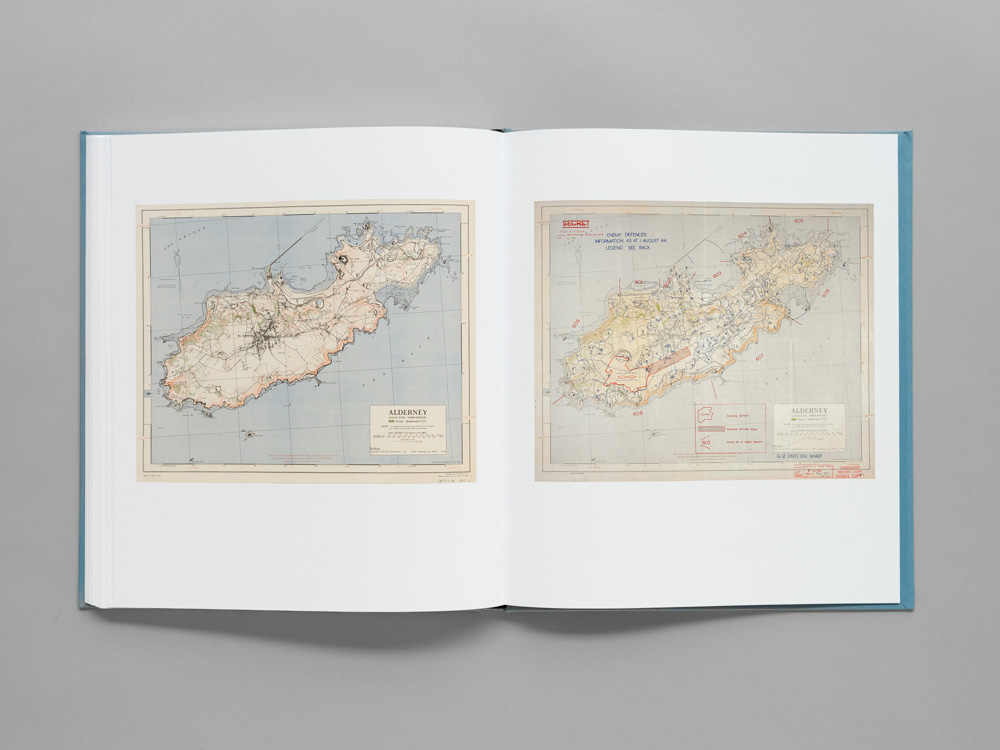

That tranquillity was shattered in 1940 when the German army advanced through Western Europe, prompting the British government to order a full civilian evacuation of Alderney. The evacuation was rapid, with the vast majority of the island’s inhabitants departing by boat from 20 to 23 June 1940, carrying only what they could manage. This decision rendered Alderney unique among occupied British territories: devoid of its local population, the island became an uninhabited canvas upon which the German military could impose its strategic and ideological imperatives. On 2 July 1940, Nazi forces occupied the island unopposed. Many islanders expected to return within months, believing that the British government would soon reclaim the Channel Islands. However, their absence stretched for five years, and their island was transformed into a site of forced labour and wartime suffering under Nazi rule, swiftly integrating it into Hitler’s vision for the Atlantic Wall, a defensive fortification system stretching along Europe’s western coastline. The island’s unoccupied status provided the German military with an unprecedented opportunity: an environment where they could construct military installations with brutal efficiency, unhindered by local resistance. To achieve this, the Nazis established a network of forced labour and concentration camps, importing thousands of prisoners from across Europe to build fortifications under appalling conditions.

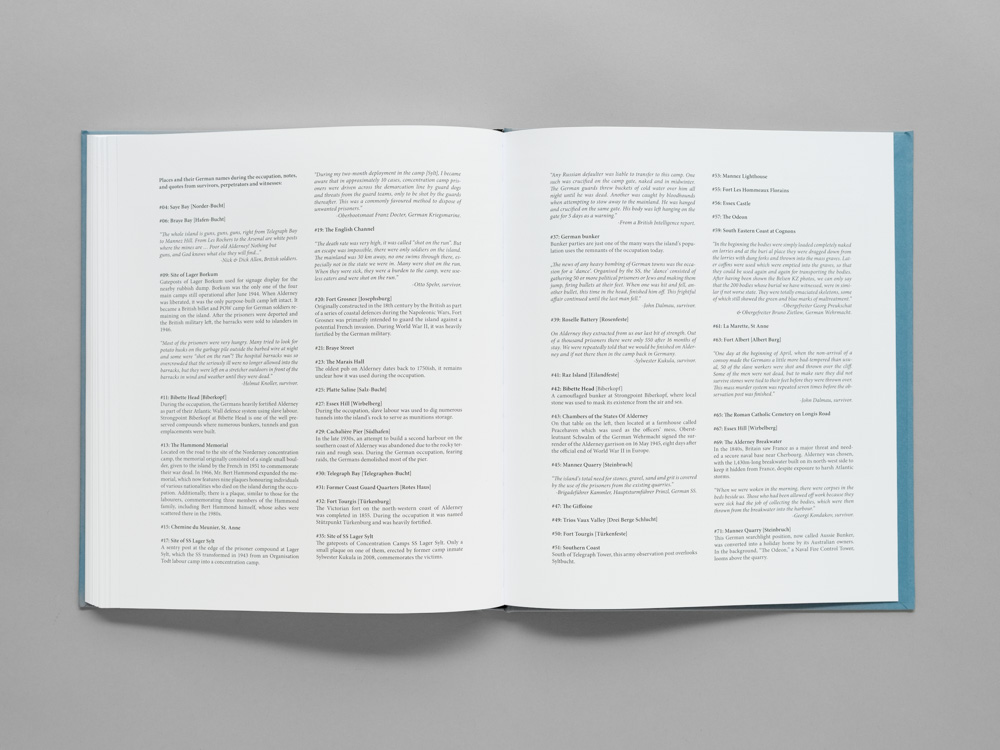

Under Nazi rule, Alderney became the site of an extensive forced labour and concentration camp system, overseen by both the Organisation Todt and the SS. The island hosted four primary camps named after German islands, each serving a distinct function within the broader framework of German occupation policies. Helgoland primarily housed Eastern European forced labourers engaged in construction projects. Norderney held a diverse mix of labourers, including French Jews and Spanish Republicans, subjected to extreme coercion. Borkum, though officially a labour camp for German volunteers under the Organistaion Todt, also housed forced labourers. The most notorious of these camps was Sylt, which began as a forced labour camp but was reclassified as a concentration camp in 1943, falling under the jurisdiction of the SS and directly linked to Neuengamme, a larger concentration camp in Germany.

“On Alderney they extracted from us our last bit of strength. Out of a thousand prisoners there were only 550 after 16 months of stay. We were repeatedly told that we would be finished on Alderney and if not there then in the camp back in Germany.”

-Sylwester Kukula, survivor.

Sylt was commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Maximilian List, an architect and long-time Nazi Party member who had joined the SS in 1930. As camp commander, List oversaw brutal conditions, executions, and harsh disciplinary measures. In March 1943, List oversaw the transfer of 1,000 prisoners from Neuengamme to Sylt, returning 200 shortly after due to their physical collapse from malnutrition and overwork. Although a disciplinary investigation was launched after several prisoners escaped during transport, the case against List and his deputy, SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Klebeck, was ultimately dropped in October of that year. List was later reassigned to Norderney and replaced at Sylt by SS-Obersturmführer Georg Braun in March 1944. Despite survivor testimonies implicating him in execution orders, he escaped prosecution and lived untroubled until his identity was exposed by journalist Solomon Steckoll in 1982. He died near Hamburg later that decade, having never stood trial for his crimes. Many other Nazi personnel who had served in Alderney similarly avoided justice, as British and Soviet authorities deprioritised war crimes prosecutions related to the island in the broader context of post-war geopolitics. This lack of accountability remains a key issue in the historical assessment of Alderney’s occupation and the atrocities committed in its camps.

Alderney’s labour force comprised a diverse demographic of coerced workers, political prisoners, Jewish deportees, and prisoners of war. While the Organisation Todt oversaw much of the island’s military construction, the SS managed the more punitive and exterminatory aspects of the occupation. Prisoners endured gruelling workdays on meagre and nutritionally deficient rations. Beatings, psychological torment, and executions were routine, fostering a climate of perpetual terror. Jewish prisoners suffered especially inhumane treatment, reflecting the broader racial hierarchies and fatal logic of the Nazi regime. The composition of Alderney’s imprisoned population mirrored Nazi policies of forced labour across occupied Europe. Soviet prisoners of war and civilians abducted from Eastern Europe faced conditions tantamount to a death sentence under Hitler’s directive for the annihilation of ‘Untermenschen.’ At least 590 French Jews were deported to Alderney in 1943, part of the larger effort to exploit and eradicate European Jewry. Spanish Republicans, exiled anti-fascist combatants from the Spanish Civil War, also found themselves ensnared in this system. Survivor testimonies depict an environment of unrelenting brutality, with many prisoners executed under fabricated pretexts of escape attempts.

“When we were woken in the morning, there were corpses in the beds beside us. Those who had been allowed off work because they were sick had the job of collecting the bodies, which were then thrown from the breakwater into the harbour.”

-Georgi Kondakov, survivor.

Mortality rates on the island remain a subject of debate. Major Theodore Pantcheff, one of the first to investigate Alderney’s camps after the war, reported 389 deaths, though his estimates have since been challenged due to suspicions of political interference and the British government’s reluctance to publicise the full extent of Nazi crimes committed on British soil. Other British investigations placed the number of deaths between 700 and 1,000, while Soviet sources, considering the large number of Eastern European victims, have claimed figures exceeding 5,000. Precise accounting has proven difficult due to the destruction of records, rapid repatriation of survivors, and the lack of civilian witnesses. To address these long-standing discrepancies, a comprehensive expert review was launched in 2024 under the leadership of Lord Eric Pickles, the UK’s Special Envoy for Post-Holocaust Issues. The review panel, comprising thirteen international experts, relied on archival records, survivor accounts, and forensic investigations to re-examine Alderney’s wartime history. It found that between 7,608 and 7,812 labourers had been brought to the island, primarily to construct its fortifications. While the review reaffirmed the severity of the abuses, it also sought to clarify certain misconceptions, notably rejecting the claim that Alderney had functioned as an extermination camp. The revised death toll ranged from 641 to 1,027, with an upper limit of 1,134 when deaths related to prisoner transport were included.

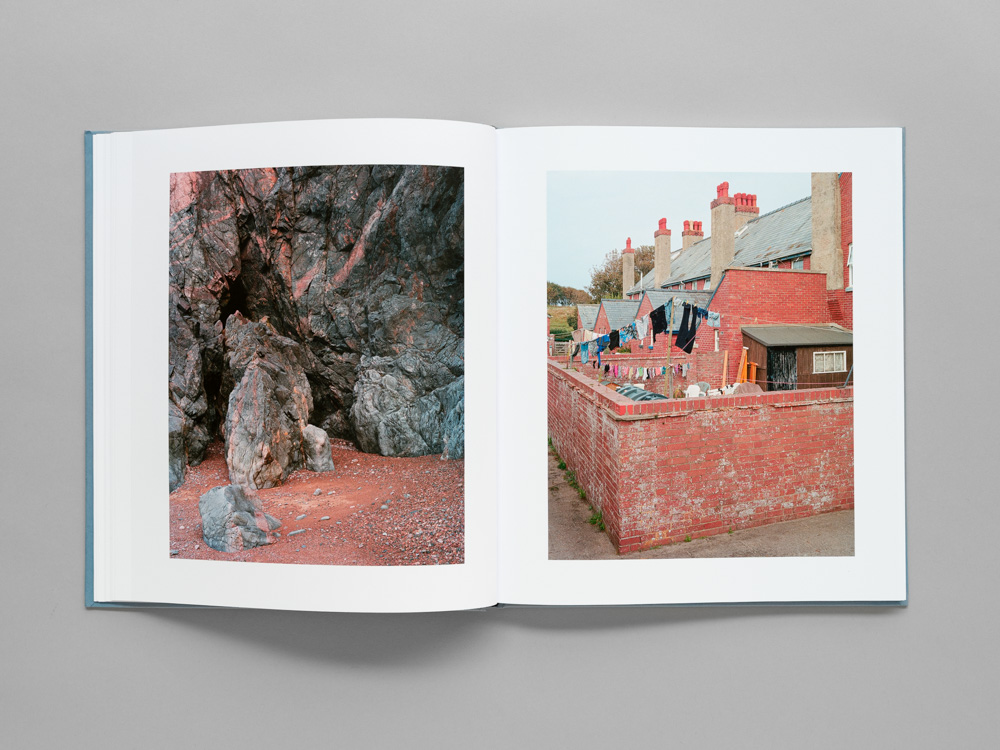

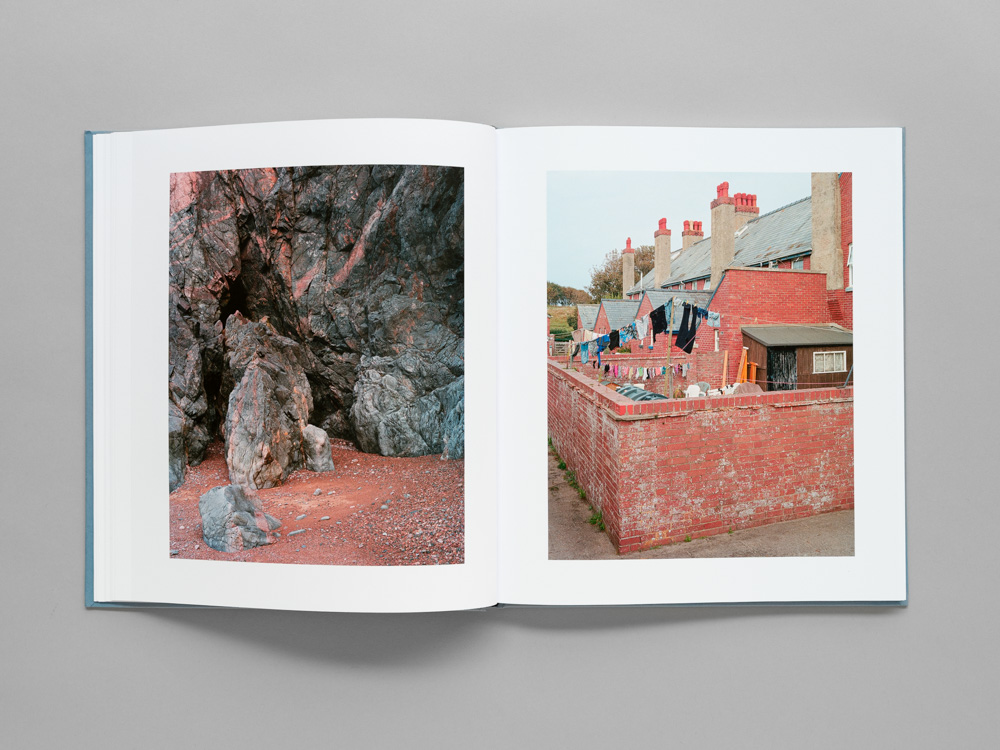

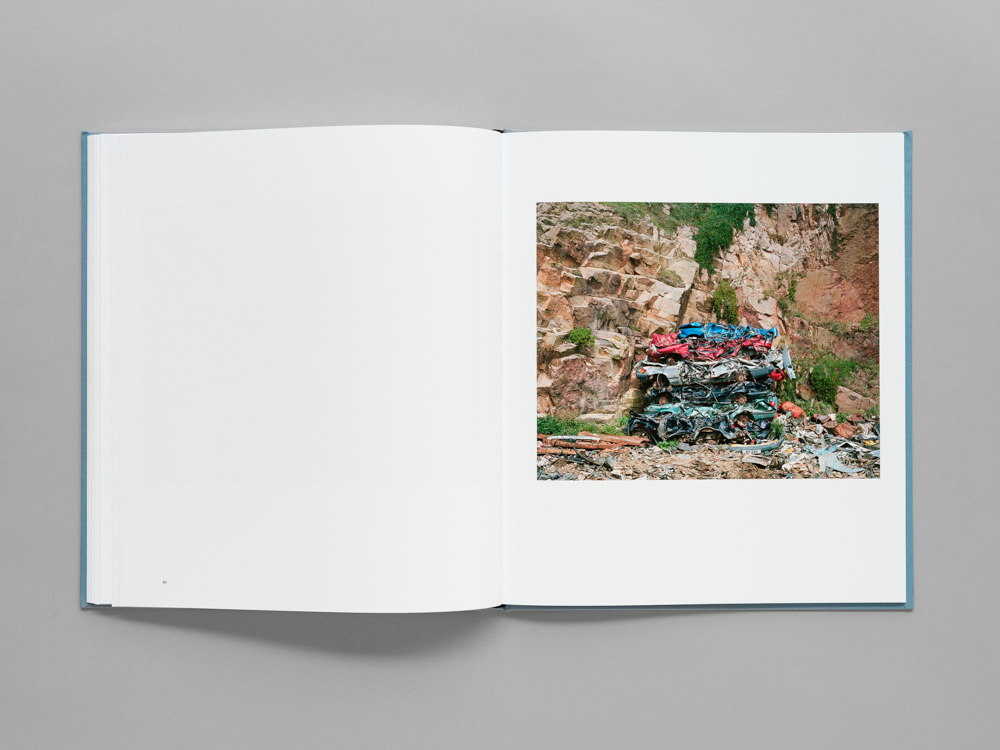

By mid-1944, as the Allied advance accelerated, the Nazis began dismantling the camps and transferring prisoners back to mainland Europe in anticipation of an Allied invasion. By June, many were sent to other forced labour sites or death camps; those too weak to move were abandoned to die. When British forces reclaimed Alderney on 16 May 1945 without combat, they found an unrecognisable landscape, scarred by fortifications, trenches, tunnels, abandoned barracks, and mass graves, the remnants of a brutal forced labour system. Returning residents faced a transformed homeland, its infrastructure devastated and its soil littered with wartime debris. The psychological toll was immense. Some never returned, unable to reconcile their memories of home with the horrors that had unfolded in their absence. Civil servants even proposed that the island be converted into a permanently uninhabited firing range.

“On Alderney, people were treated like cattle; there was no hope of surviving. I was called number 146, no one ever used my name. Once I dreamt I was being eaten by a German, and I was so desperate to escape that I put out my arms as wings to fly, and then I saw the sea beneath me and found I was too weak to fly; I was terrified of falling into the sea.”

-Alexei Ikonnikov, survivor.

In recent years, archaeological research has played a key role in uncovering the fuller history of the island’s occupation. Scholars such as Caroline Sturdy Colls have employed non-invasive geophysical techniques to locate unmarked burial sites and reconstruct the layouts of long-destroyed camps, providing crucial confirmation of survivor testimonies and archival records. These efforts have helped bridge longstanding gaps in the historical narrative, though much remains unknown.

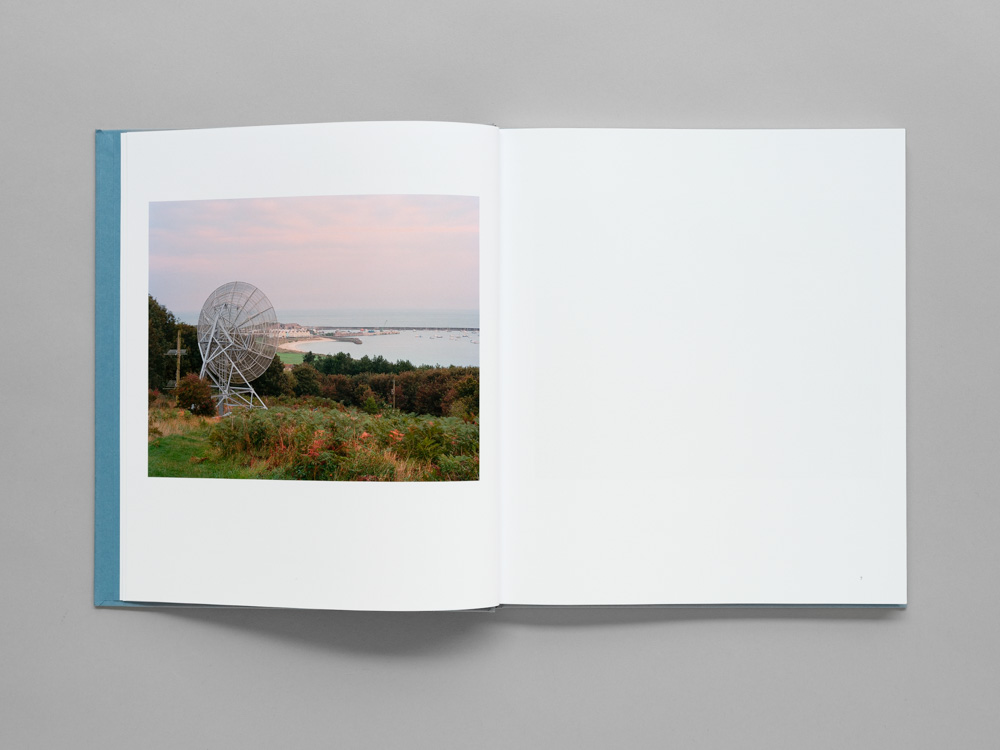

Alderney today is home to around 2,000 residents and operates under its own legislature within the Bailiwick of Guernsey. Its economy relies largely on tourism, agriculture, and financial services, and life on the island is quiet and remote. Yet public awareness of Alderney’s role in the Nazi forced labor and concentration camp system remains limited and the need for remembrance and recognition remains.

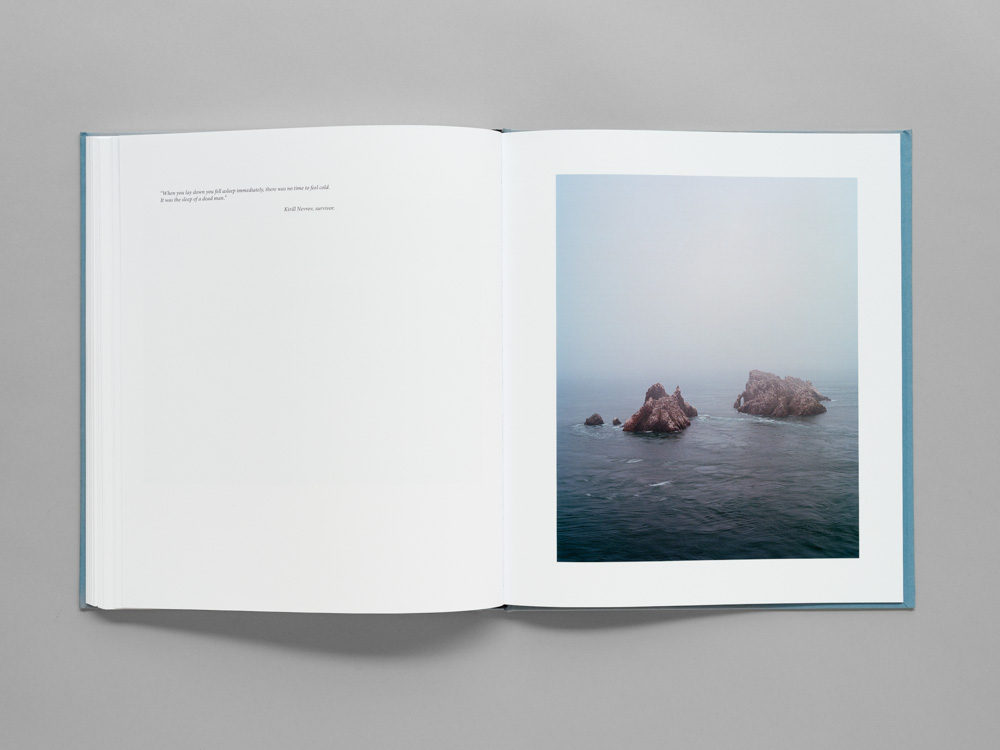

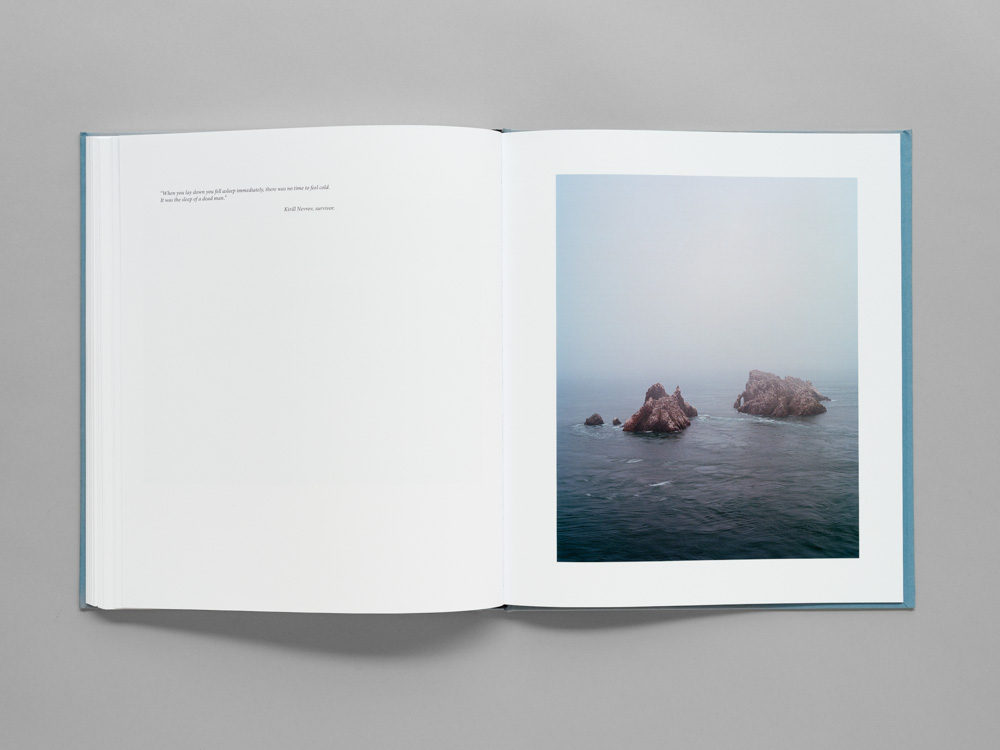

“When you lay down you fell asleep immediately, there was no time to feel cold. It was the sleep of a dead man.”

Kirill Nevrov, survivor.

"Don't Mention The War", published by Super/Carta / 108 pp / 260 x 233mm

Order directly from my shop

Don't mention the war.

(2015–2018)

Alderney, the northernmost of the Channel Islands, occupies a unique and liminal space between Britain and continental Europe, both geographically and historically. Spanning approximately 7.8 square kilometres (3 square miles), the island was home to around 1500 inhabitants before the outbreak of the Second World War. As a sparsely populated British Crown dependency, it maintained a quiet agrarian economy while holding military significance due to its strategic position in the English Channel undisturbed by the political turmoil brewing across Europe.

“The Germans started shooting prisoners who were stealing potatoes out of the fields, but the desire for food was much stronger than the fear of death. We were determined to defy the will of the Germans who had told us that no one would leave the island alive.”

Georgi Kondakov, survivor.

That tranquillity was shattered in 1940 when the German army advanced through Western Europe, prompting the British government to order a full civilian evacuation of Alderney. The evacuation was rapid, with the vast majority of the island’s inhabitants departing by boat from 20 to 23 June 1940, carrying only what they could manage. This decision rendered Alderney unique among occupied British territories: devoid of its local population, the island became an uninhabited canvas upon which the German military could impose its strategic and ideological imperatives. On 2 July 1940, Nazi forces occupied the island unopposed. Many islanders expected to return within months, believing that the British government would soon reclaim the Channel Islands. However, their absence stretched for five years, and their island was transformed into a site of forced labour and wartime suffering under Nazi rule, swiftly integrating it into Hitler’s vision for the Atlantic Wall, a defensive fortification system stretching along Europe’s western coastline. The island’s unoccupied status provided the German military with an unprecedented opportunity: an environment where they could construct military installations with brutal efficiency, unhindered by local resistance. To achieve this, the Nazis established a network of forced labour and concentration camps, importing thousands of prisoners from across Europe to build fortifications under appalling conditions.

Under Nazi rule, Alderney became the site of an extensive forced labour and concentration camp system, overseen by both the Organisation Todt and the SS. The island hosted four primary camps named after German islands, each serving a distinct function within the broader framework of German occupation policies. Helgoland primarily housed Eastern European forced labourers engaged in construction projects. Norderney held a diverse mix of labourers, including French Jews and Spanish Republicans, subjected to extreme coercion. Borkum, though officially a labour camp for German volunteers under the Organistaion Todt, also housed forced labourers. The most notorious of these camps was Sylt, which began as a forced labour camp but was reclassified as a concentration camp in 1943, falling under the jurisdiction of the SS and directly linked to Neuengamme, a larger concentration camp in Germany.

“On Alderney they extracted from us our last bit of strength. Out of a thousand prisoners there were only 550 after 16 months of stay. We were repeatedly told that we would be finished on Alderney and if not there then in the camp back in Germany.”

-Sylwester Kukula, survivor.

Sylt was commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Maximilian List, an architect and long-time Nazi Party member who had joined the SS in 1930. As camp commander, List oversaw brutal conditions, executions, and harsh disciplinary measures. In March 1943, List oversaw the transfer of 1,000 prisoners from Neuengamme to Sylt, returning 200 shortly after due to their physical collapse from malnutrition and overwork. Although a disciplinary investigation was launched after several prisoners escaped during transport, the case against List and his deputy, SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Klebeck, was ultimately dropped in October of that year. List was later reassigned to Norderney and replaced at Sylt by SS-Obersturmführer Georg Braun in March 1944. Despite survivor testimonies implicating him in execution orders, he escaped prosecution and lived untroubled until his identity was exposed by journalist Solomon Steckoll in 1982. He died near Hamburg later that decade, having never stood trial for his crimes. Many other Nazi personnel who had served in Alderney similarly avoided justice, as British and Soviet authorities deprioritised war crimes prosecutions related to the island in the broader context of post-war geopolitics. This lack of accountability remains a key issue in the historical assessment of Alderney’s occupation and the atrocities committed in its camps.

Alderney’s labour force comprised a diverse demographic of coerced workers, political prisoners, Jewish deportees, and prisoners of war. While the Organisation Todt oversaw much of the island’s military construction, the SS managed the more punitive and exterminatory aspects of the occupation. Prisoners endured gruelling workdays on meagre and nutritionally deficient rations. Beatings, psychological torment, and executions were routine, fostering a climate of perpetual terror. Jewish prisoners suffered especially inhumane treatment, reflecting the broader racial hierarchies and fatal logic of the Nazi regime. The composition of Alderney’s imprisoned population mirrored Nazi policies of forced labour across occupied Europe. Soviet prisoners of war and civilians abducted from Eastern Europe faced conditions tantamount to a death sentence under Hitler’s directive for the annihilation of ‘Untermenschen.’ At least 590 French Jews were deported to Alderney in 1943, part of the larger effort to exploit and eradicate European Jewry. Spanish Republicans, exiled anti-fascist combatants from the Spanish Civil War, also found themselves ensnared in this system. Survivor testimonies depict an environment of unrelenting brutality, with many prisoners executed under fabricated pretexts of escape attempts.

“When we were woken in the morning, there were corpses in the beds beside us. Those who had been allowed off work because they were sick had the job of collecting the bodies, which were then thrown from the breakwater into the harbour.”

-Georgi Kondakov, survivor.

Mortality rates on the island remain a subject of debate. Major Theodore Pantcheff, one of the first to investigate Alderney’s camps after the war, reported 389 deaths, though his estimates have since been challenged due to suspicions of political interference and the British government’s reluctance to publicise the full extent of Nazi crimes committed on British soil. Other British investigations placed the number of deaths between 700 and 1,000, while Soviet sources, considering the large number of Eastern European victims, have claimed figures exceeding 5,000. Precise accounting has proven difficult due to the destruction of records, rapid repatriation of survivors, and the lack of civilian witnesses. To address these long-standing discrepancies, a comprehensive expert review was launched in 2024 under the leadership of Lord Eric Pickles, the UK’s Special Envoy for Post-Holocaust Issues. The review panel, comprising thirteen international experts, relied on archival records, survivor accounts, and forensic investigations to re-examine Alderney’s wartime history. It found that between 7,608 and 7,812 labourers had been brought to the island, primarily to construct its fortifications. While the review reaffirmed the severity of the abuses, it also sought to clarify certain misconceptions, notably rejecting the claim that Alderney had functioned as an extermination camp. The revised death toll ranged from 641 to 1,027, with an upper limit of 1,134 when deaths related to prisoner transport were included.

By mid-1944, as the Allied advance accelerated, the Nazis began dismantling the camps and transferring prisoners back to mainland Europe in anticipation of an Allied invasion. By June, many were sent to other forced labour sites or death camps; those too weak to move were abandoned to die. When British forces reclaimed Alderney on 16 May 1945 without combat, they found an unrecognisable landscape, scarred by fortifications, trenches, tunnels, abandoned barracks, and mass graves, the remnants of a brutal forced labour system. Returning residents faced a transformed homeland, its infrastructure devastated and its soil littered with wartime debris. The psychological toll was immense. Some never returned, unable to reconcile their memories of home with the horrors that had unfolded in their absence. Civil servants even proposed that the island be converted into a permanently uninhabited firing range.

“On Alderney, people were treated like cattle; there was no hope of surviving. I was called number 146, no one ever used my name. Once I dreamt I was being eaten by a German, and I was so desperate to escape that I put out my arms as wings to fly, and then I saw the sea beneath me and found I was too weak to fly; I was terrified of falling into the sea.”

-Alexei Ikonnikov, survivor.

In recent years, archaeological research has played a key role in uncovering the fuller history of the island’s occupation. Scholars such as Caroline Sturdy Colls have employed non-invasive geophysical techniques to locate unmarked burial sites and reconstruct the layouts of long-destroyed camps, providing crucial confirmation of survivor testimonies and archival records. These efforts have helped bridge longstanding gaps in the historical narrative, though much remains unknown.

Alderney today is home to around 2,000 residents and operates under its own legislature within the Bailiwick of Guernsey. Its economy relies largely on tourism, agriculture, and financial services, and life on the island is quiet and remote. Yet public awareness of Alderney’s role in the Nazi forced labor and concentration camp system remains limited and the need for remembrance and recognition remains.

“When you lay down you fell asleep immediately, there was no time to feel cold. It was the sleep of a dead man.”

Kirill Nevrov, survivor.

"Don't Mention The War", published by Super/Carta / 108 pp / 260 x 233mm

Order directly from my shop

Impressum & Datenschutz | (c) Martin Friedrich 2025